In This Article, We'll Cover:

- The History of Sunscreen

- The Difference Between Chemical & Mineral Sunscreens

- Sunscreen Problems & Misconceptions

- Greenwashing in the Sunscreen Industry

- Why European Sunscreens Might Be Better

- How i Healthy’s Favorite Mineral Sunscreens & Why

Sunscreen protects your skin, right? Well, maybe not.

Turns out conventional sunscreen can be harmful to the environment and us. Up to 14,000 tons of sunscreen passes through coral reefs. Every year. Devastating them. (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 62)

But I’ve had skin cancer. So, I am not going without sunscreen, nor will I advocate not using it.

So what to do?

We use something that works and doesn’t harm our bodies or the planet.

Sounds nice! Let’s wade into these waters.

Sunscreens, Swimsuits, & Tanning: A Brief History

Let’s talk sun. The interconnectedness of cultural values on skin color, modesty, and swimsuits is hard to ignore.

Sunscreen Orgin Story

Skin cancer and radiation weren’t specifically on ancient people’s radars. But cosmetic considerations, like sun damage, sun burns, and skin darkening were. (45)

For centuries, pale skin was a mark of wealth and beauty, whereas darker skin meant manual labor, lower class, and poverty. (82)

Lead-based cosmetics, dating as far back as the ancient Romans, were used to lighten skin. And centuries later, bleach creams were used to remove tans. (82)

To some cultures around the world, lighter skin color equaled wealth. This need to be pale influenced fashion and cosmetics for centuries.

Ancient peoples protected against the sun in many ways. And some are still practiced by Indigenous Peoples today:

- Borak or burak is a paste of waterweeds, rice, and spices. It’s still used by the Sama-Bajau people.

- Olive oil applied to skin by the ancient Greeks. Research now shows olive oil provides some (but still inadequate) UV protection.

- Rice bran, jasmine, and lupine applied to skin in ancient Egypt. A combination we now know can absorb UV light, repair DNA damage, and lighten skin.

- Some Indigenous Peoples used Tsuga canadensi, a type of pine needle.

- Thanaka, is a paste made from ground bark that is antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and absorbs UV rays. The peoples of Myanmar have used thanaka for over 2000 years.

(44, 45, 48, 49, 83, 84, 85)

Clothing offered (sometimes unintended) sun protection too:

- Colder climates meant more clothing to stay warm and thus skin coverage.

- Cultural values. Some societies expected modesty resulting in less exposed skin.

- Hats, parasols, veils, depicted in artistic works across the world, provided physical barriers to sun exposure.

(46, 82)

For centuries, many cultural around the world valued lighter skin. And some of those same cultures valued modesty. Which meant covering up.

From Bathing Gowns to Bikinis

Let’s talk about modesty values, specifically swimsuits. It’s hard to talk about sunscreen without talking about swimsuits.

Modesty values influenced not only fashion, but sun protection too.

What people wore to the beach directly affected their sun exposure.

In classical antiquity, like in Rome, swimming and bathing naked was standard. But enter the modesty values of Christianity.

Bathers and swimmers alike covered up with “bathing costumes”. These were high necked, long sleeved, and went to the knees or longer. Women often wore stocking to cover any exposed leg too. The material (often wool, flannel, or linen) was dark too, so no skin could show through once wet. (79)

Some bathing gowns of the era even have lead disks sew into the hem to prevent the fabric from floating upwards while in the water. (79, 80)

Jump forward a few hundred years to the Victorian era.

Bodies were more covered than ever before. In the UK and United States, women wore petticoats and even bathing corsets. (80)

It wasn’t until the sport of swimming, especially for women, that bathing suits evolved into swimsuits. Or swim costume, as they were called first.

As more privileged people took the beach for leisure, swimming costumes became for practical to allow for greater range of motion. Sleeves and under-trousers shortened, and bathing corsets were eliminated. But many public beaches still had strict modesty requirements. (79, 80)

What really spurred change was Annette Kellerman, an Australian swimmer.

The 1896 Olympic Games allowed women to compete in swimming for the first time. And Kellerman competed in a tight-fitting swimsuit that exposed her entire arm and her legs to mid-thigh. Photos of her in her suit were published in newspapers across the world. (79)

When invited to perform in front of the British Royal Family, that same style suit was deemed too immodest to wear. Refusing to swim in a sub-par suit only to meet their modesty standards, Kellerman simply sewed in leggings to the bottom of the suit. The result was a skintight wetsuit looking costume. Very different from a swim gown. (79)

Kellerman encountered more trouble in Boston when her swimsuit was too indecent yet again. Kellerman argued that swimming in anything else would affect her performance. And in the end, she was permitted to swim in her suit unmodified. The whole incident was wildly publicized. (79)

The result of Kellerman's determination & media coverage?

The idea that women cold swim in less clothing, even without a dress, wasn’t so bad.

Fast forward to 1920s.

The rise of leisure time for affluent Americans. The more people went to beaches, the more people realized that swimsuit designs were impractical.

So swimsuits became smaller and smaller.

And by the 1930s men could compete shirtless in the Olympics, and women could compete in racerback-style one-pieces that exposed the shoulder blades. (79)

WWII was the next big influencer.

To conserve materials for the war effort, during and post war fashion trends used less fabric. The US War Production Board issued Regulation L-85, which mandated a reduction of fabric in women’s clothes.

This exposed skin in ways that hadn’t been done before. Hemline raised, sleeves shortened, necklines dropped, and swimsuits became bikinis, thanks to French influence. (80, 81)

With all that exposed skin darkening in the sun, and the help of Hollywood and fashion magazines, people’s attitudes toward tanning changed.

Suntans: A Mark of Wealth & Health

While some societies still valued pale skin, after WWII some Americans associated suntans with privilege, wealth, and the ability to take vacations. (82)

Hollywood films featuring beaches & bikinis, coupled with the expanded transportation options, fueled a vacation rush for privileged Americas. (79, 80, 82)

And advertisements in magazines like Vogue and Bazaar reinforced the glamorous “sun-kissed” life, swimsuits, and tanning. Simultaneously, those same magazines pulled skin bleaching articles and advertisements. (79, 80, 82)

Roughly around the same time as Hollywood suntan hype, the medical community in the early 20th century began to see a connection between sunlight and health. UV light and Vitamin D from sun exposure was found to prevent diseases, like tuberculosis and rickets, in children. And some physicians began to advocate UV light therapy for many different illnesses. Popular American magazines touted UV, sunlight, and tanned skin synonymous with good health. (82)

With more folks exposing their skin to the sun, a need to prevent sunburns, but not suntans, rose. (46)

Enter tanning oils.

By 1956, chemist Franz Greiter introduced the concept of SPF (sun protection factor). And UV radiation became the hot topic of the age. Products that blocked UV rays entered the market. (46)

By today’s standards, one of first sunscreens would rate about SPF 2. (46)

In the decades following, scientists have upped their SPF game.

A gradual shift from physical barriers marked a new age in sunscreen: Chemical sunscreens.

Chemical Vs. Physical Filters

Much of history’s sunscreen use physical barriers to block light.

The other method? Chemical filters. Chemical filters are what it sounds like. A mix of chemicals that absorb UV rays, convert those rays into heat, and then release them away from the body. (1)

Today’s sunscreens categorize as physical or chemical. Let’s explore them.

Physical Sunscreen: Ancient Techniques & Still Relevant!

Physical sunscreens are barriers like hats, long sleeved clothing, umbrellas, or mineral-based sunscreens (dermal application) that block UV light.

Mineral sunscreens often use zinc oxide or titanium dioxide. These minerals sit on the skin’s surface and physically block UV light. Zinc oxide paste isn’t new technology, it’s been used for thousands of years for sun protection. (1, 47)

Be sure to choose mineral sunscreens with “non-nano” particles. Nano particles can permeate the skin’s surface and may contribute genotoxicity and inflammation. (10, 11)

The texture of mineral sunscreens tends to be thicker than chemical sunscreens. They do not “rub in” well because they form a physical layer on the skin’s surface.

Mineral sunscreens need frequent reapplications, particularly when exposed to water. Follow product application guidelines for better results.

Chemical Sunscreen: So Many Chemicals!

Chemical UV blockers in sunscreen could include

- Avobenzone

- Benzophenone

- Ethylhexyl salicylate

- Homosalate

- Octinoxate

- Octisalate

- Octocrylene

- Oxybenzone

(1)

This list is concerning.

Benzophenone as a carcinogen (2). Benzophenone is also an endocrine and hormone disruptor detectable in breast milk and urine. (23, 24, 25)

Oxybenzone links to coral reef bleaching, algae die off, neurotoxicity, and marine life infertility. (3, 4, 5, 6)

Plus, chemical sunscreens often contain other red flags like:

- 1, 4-Dioxane contamination

- Benzocaine

- Benzene

- BPA

- Fragrance/Phthalates

- Parabens

- PEG Compounds

- Preservatives

(5, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43

The Chemicals Guide explains in more detail and offers options to better avoid exposure.

Chemical based sunscreens absorbed into the body and remain detectable in the blood up to 21 days after exposure, according to an FDA-lead study in 2019. (16)

That’s concerning for many reasons. A big one? Benzene, a known carcinogen, was detected in 27% of tested sunscreens in 2021 (66). Ironic that something to prevent skin cancer could potentially cause another kind of cancer.

Not only can these chemicals absorb into our bodies, but they can also wash off into our water sources and cause environmental harm. If it goes on your skin, it goes into our oceans. This concern has spurred legislative reform across the world.

The Republic of Palau for example, under Senate Bill No. 10-135, SD1, HD1, banned sunscreens containing:

- 4-methyl-benzylidene camphor

- Benzyl paraben

- Butyl paraben

- Ethyl paraben

- Triclosan

- Methyl paraben

- Octinoxate (octyl methoxycinnamate)

- Octocrylene

- Oxybenzone (benzophenone-3)

- Phenoxyethanol

(8)

Hawaii, Key West, US Virgin Islands, Bonaire, and Aruba in recent years have followed suit with their own sunscreen bans. The list keeps growing. (9, 63, 64)

Less chemical sunscreens, yay! If only things were that simple…

Problems with Sunscreens

Sunscreens, no matter their ingredients, have a few issues we need to highlight.

First. The “reef-friendly” and “reef-safe” buzzwords.

Greenwashing Alert: What is Reef-Friendly?

As well-intending as it may be, “reef-friendly” is just an unregulated term. (58, 61)

It’s the “all natural” of sunscreens. The “body-safe” of Greenwashed Sex Toys. Without a third-party certificated, there’s not much validity to the claim. (58, 61)

It’s no surprise that nearly half of “reef-safe” sunscreens tested didn’t pass The National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration reef-safe standards. (61)

That’s where Protect Land + Sea Certified comes in.

Products with this certification mark are independently tested by Haeretics Environmental Laboratory (HEL), a nonprofit lab dedicated to wildlife and ecosystem conservation. (59, 60)

This mark means a sunscreen has no:

- Microplastics or Nanoparticles

- Oxybenzone, Octinoxate

- 4-Methylbenzylidene Camphor, Octocrylene

- Para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA)

- Methyl Paraben, Ethyl Paraben, Propyl Paraben, Butyl Paraben, Benzyl Paraben

- Triclosan

(59, 60)

Very few sunscreens have this certification.

American vs. European UVA Standards & Cancer Misunderstandings

Only 11 out of 20 American sunscreens tested passed European Union sunscreen standards, according to a study by the American Academy of Dermatology. (17)

That discrepancy is scary.

European sunscreens have higher UVA protections than the US. (17)

Does that mean buying European sunscreen is better?

Not necessarily.

Let’s talk about UVA vs UVB Radiation. What’s the Difference?

Radiation, in regard to the sun, has two types:

- Ultraviolet A (UVA) Radiation:

- Short wavelengths.

- While less intense than UVB, UVA penetrates the skin more deeply.

- Linked to skin aging, wrinkles, and nonmelanoma skin cancers.

- Used in tanning beds.

- Can penetrate glass and clouds.

- “Full spectrum” sunscreen offers protection against UVA radiation.

- Ultraviolet B (UVB) Radiation:

- Longer wavelengths.

- Penetrates outermost layers of the skin.

- Linked to skin burning and blistering.

- Does not penetrate glass, but reflects off snow or water.

- Is often what SPF (Sun Protection Factor) refers to.

(19)

When we think radiation, we might think about cancer.

Sunscreen and skin cancer have a link that’s been long misunderstood.

Historically, experts thought UVB radiation caused skin cancer. So, developers produced sunscreens with predominantly UVB protections. These UVB protections have a rating called SPF, or Sun Protection Factor.

Experts now think UVA radiation plays a bigger role in cancers than previously thought. This exposes the gaps in American SPF standards. (23)

American sunscreen SPF primarily protects against UVB. There are “full spectrum” sunscreens that claim both UVA and UVB protections.

American “full spectrum” sunscreens still allow three times more UVA radiation than European sunscreens. (18)

While some American approved sunscreens may prevent sunburns caused by UVB radiation, they may not protect from cancer causing UVA radiation.

According to one study, a fair-skinned person using UVB blocking sunscreen over a 2-week vacation could expose themselves to UVA radiation equal to ten tanning bed sessions. (27)

Sunscreens with higher SPF ratings link to longer non-burning sun exposure. And thus longer UVA exposure. (20, 21)

Rates of melanoma have increased 1.5% each year for the last 10 years despite increased use of sunscreens, according to the National Cancer Institute. (29)

Why?

One theory: People stay out in the sun longer because they don’t burn. But the sunscreen only blocks UVB radiation. So, UVA exposure and by extension, cancer risk, increases.

Using UVB blocking sunscreen could promote a false sense of protection. We might not get a sunburn, but we might expose ourselves to UVA radiation instead. (20, 21)

So, Does SPF Even Matter?

Australian SPF claims fell short of Australia’s rigorous sunscreen requirements, according to Choice, an Australian consumer watchdog. Australia has some of the highest UV exposure incidences. Roughly, two in three Australians could be diagnosed with skin cancer before age of 70. (23)

Similar studies in both the UK and USA show SPF ratings failed to live up to their claims. (23)

In Norway, sunscreen use from 1997 to 2007 increased, but sunburn incidences did not decrease. (23)

The FDA recommends using “SPF60+”, citing that higher SPF ratings could be “inherently misleading”. (28)

Until there is better accountability to SPF claims, consumers are a bit on their own.

Does Sunscreen Really Block Vitamin D Production?

I’ve seen the claim: “sunscreen blocks vitamin D production and can cause vitamin D deficiencies!!!”

Hmmm. Let’s see what the research says.

Vitamin D synthesizes in the body when exposed to UVB rays. Vitamin D plays a role in skeletal health. (33, 35)

Vitamin D deficiency affects almost 1 billion people worldwide. Deficiency might link to cancer, heart disease, rickets, osteoporosis, autoimmune disease, and depression. (33)

Higher levels of melanin may link to deficiency, due to lower absorption through the skin. Other causes for low absorption can include celiac disease, cystic fibrosis, liver disease, kidney disease, and some medication use. (33)

A 2019 review in the British Journal of Dermatology looked at four studies, three field trials, and 69 observational studies from 1970-2017. The review conclusion? Sunscreen use did not decrease vitamin D levels. But the reviewers agreed that most sunscreens tested were lower SPFs. There was a lack of high-SPF sunscreen studies. (30)

The publication also noted that one study did link sunscreen to lower vitamin D production. But the review cited concerns about the UV light used in the study. Artificially generated, the UV light output was not equal to Earth’s sunlight. (30)

A 2019 publication in the British Journal of Dermatology tested vitamin D levels of two groups of participants. The first group had a 1-week sunny holiday, the other group did not. Both groups used the same sunscreen. The results?

- SPF 15 sunscreen protected against sunburn in both groups.

- Vitamin D synthesis was significantly higher in the sunny vacation group.

- Sunscreen use and safe deliberate sun exposure does not hinder vitamin D synthesis. But sunscreen use and limited sun exposure might.

(31)

A third study in the British Journal of Dermatology also concludes that regular sunscreen use does not hinder vitamin D levels. (32)

The consensus from experts like the Skin Cancer Foundation, conclude that sunscreen does not prevent vitamin D synthesis nor contribute to vitamin D deficiency. (35)

The Skin Cancer Foundation further explains that proper vitamin D levels can be maintained with regular sunscreen use because sunscreen does not filter out UVB rays 100%. As much as 2-7% of UVB rays can penetrate our skin even with sunscreen use. (35)

If you are concerned about vitamin D levels consult your physician.

My Favorite Mineral Sunscreens

Before we dive into my favorite brands, what else matters for sunscreen products?

The How i Healthy Standard

Our favorite products/brands meet as many of these conditions as possible.

Healthy body, healthy planet, & healthy sex means:

- Align with My Best Sustainability & Ethical Tips

- As Local as Possible

- Cruelty-Free

- Doesn’t Contain these Harmful Chemicals

- Environmental and/or Socially Responsible Company

- Ethically Made: Fair Trade, Living Wages, Safe Worker Conditions

- Gender-inclusive

- No Greenwashing Scams

- Organic & Sustainably Harvested Ingredients

- Pass How i Healthy’s Counterfeit Vetting Process

- Purchased Through/From an Ethical Shop/Marketplace.

- Zero Waste / Plastic & Bioplastic-free / Home Compostable

- 1% for the Planet®, B Corporation®, Green American Business®, or similar credentials

With that in mind, there’s two brands I use. One for face sunscreen, and the other for body sunscreen.

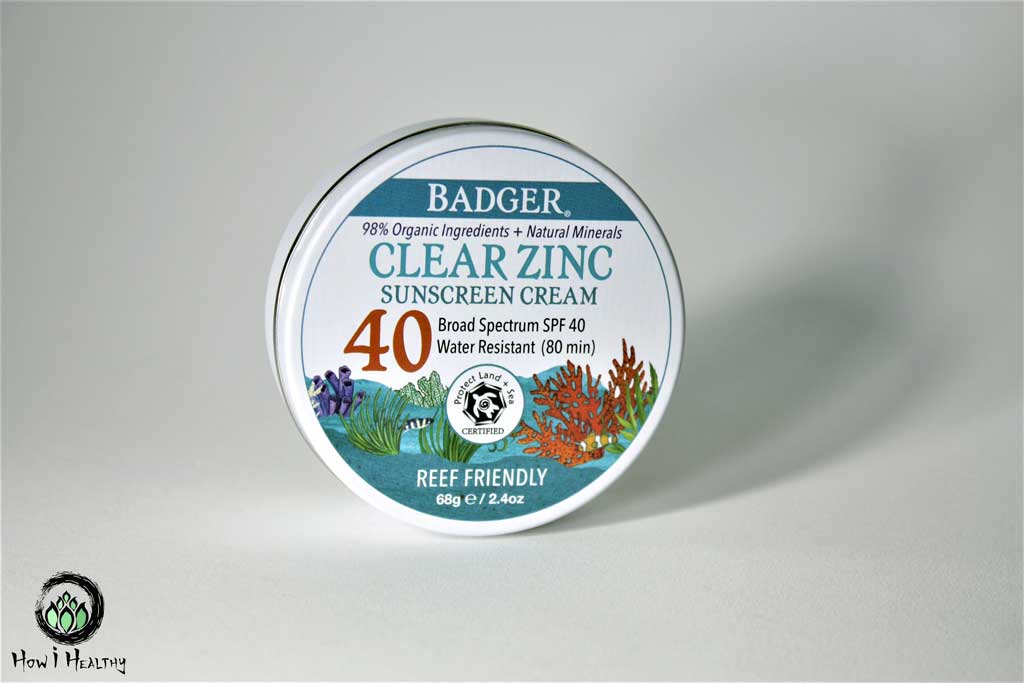

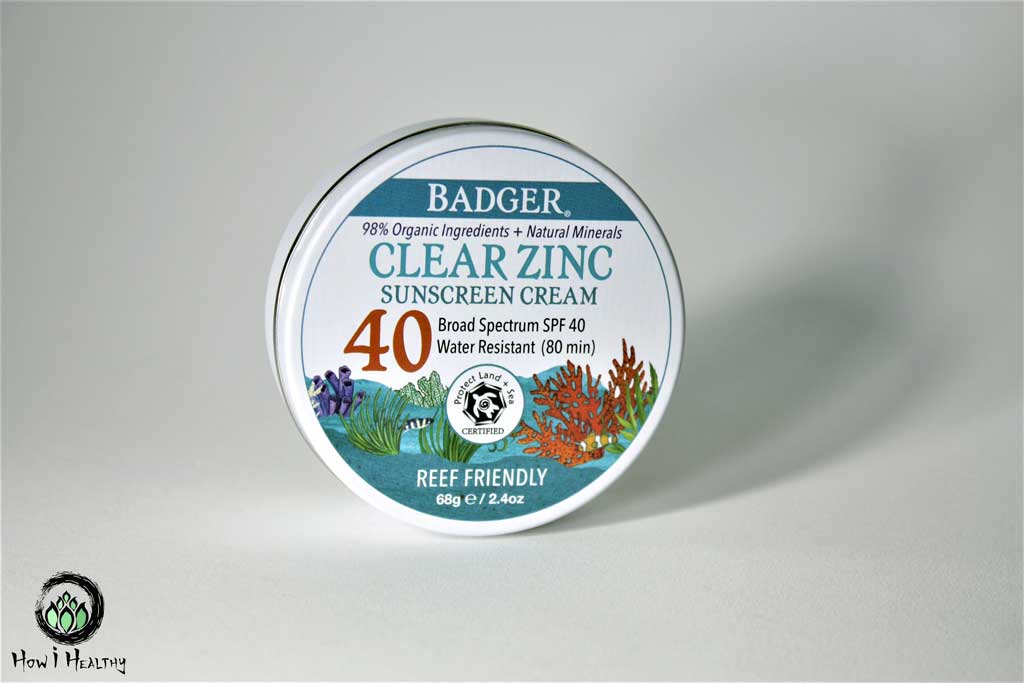

Badger® Clear Zinc Mineral Sunscreen

Product Kudos

Origin: USA.

End of Life: Recycle or reuse tin.

Ingredients/Packaging:

- Badger® Clear Zinc SPF 40: Uncoated Zinc Oxide 22.5%, Organic Sunflower Oil, Organic Beeswax, Sunflower Vitamin E. (54)

- Packed in a recyclable metal tin.

Note: there is a small band of plastic sealing the container due to FDA sunscreen packaging requirements.

Why It’s Awesome:

- Actually reef-friendly. With the Protect Land + Sea Certification, this sunscreen has lab results to back up their claims. (59, 60)

- Clear! Unlike many mineral sunscreens, this one has no white caste.

- Fragrance Free. I hate putting on sunscreen and smelling like a fruit.

- Not the most expensive sunscreen I’ve seen, but not the cheapest either. I make a tin last by covering up with a rash guard and hat.

- SPF 40 UVA and UVB broad-spectrum protection up to 80 minuets.

- Thick, but non-greasy. It’ll take a back rub to get this in. That’s fine with me!

Company Kudos

- Badger® is groovy. Since 1995, this New Hampshire based family-owned, family-run, Certified B Corp has taken social and environmental stewardship seriously. (52)

- Badger®’s products are made in the USA and are Leaping Bunny Certified. Most products are also certified organic and/or Fair Trade. No wonder Badger® makes several of My Favorite Products.

- Donates 10% of before tax profits to educational and community nonprofits. (55)

- Family friendly policies include primary & secondary care parental leave, extended parental leave, childcare reimbursements, and partially subsidized on-sight daycare. There’s even a “take your babies to work” policy where infants up to 6 months can join their parent in the office. (53)

Earth Harbor Eclipse Clear Zinc Mineral Sunscreen

I know! Two sunscreens?!

I’m the last person to use two products for the same thing. I’m a minimalist.

But hear me out.

Badger® sunscreen and Earth Harbor aren’t the same.

I tried to use Badger® daily for my face and ended up breaking out. It was to the point where I avoided using sunscreen on my face!

That’s not good. I’ve had skin cancer; I need to wear sunscreen.

So, I hunted for a lightweight & plastic-free option. I found Earth Harbor’s Eclipse Mineral Sunscreen. Now I WANT to put on sunscreen. I actually look forward to it! This sunscreen is no chore. It’s an joy.

And it’s too expensive to put all over my body…hence Badger®.

Product Kudos

Origin: Utah, USA.

End of Life: Recyclable glass bottle and jar. Plastic tops depends on community recycling standards. OR you can opt for refills directly from Earth Harbor and reuse the plastic tops! The refills are capped with easy-to-recycle aluminum tops that you swap out for your old plastic tops.

Ingredients/Packaging:

- Earth Harbor Eclipse Sunscreen: Zinc Oxide (18.9%), Water (Aqua), Caprylic/Capric Triglyceride (plant-based conditioner), Coconut Alkanes (coconut-derived emollient), Cetearyl Alcohol (plant-derived fatty alcohol), Vegetable Glycerin, Aloe Leaf (Aloe barbadensis) Juice, Coco-Glucoside (plant-derived thickener), Cetearyl Glucoside (plant-derived emulsifier), Caprylyl/Capryl Glucoside (plant-based conditioner), Dipotassium Glycyrrhizate (licorice root-derived moisturizer), Green Tea (Camellia sinensis) Leaf Extract, Algae (Laminaria saccharina) Extract, Shea (Butyrospermum parkii) Butter, Hydrolyzed Jojoba Esters, Coco-Caprylate/Caprate (plant-derived emulsifier), Polyhydroxystearic Acid (fatty acid), Polyglyceryl-3 Polyricinoleate (natural emulsifier), Isostearic Acid (plant-derived emollient), Sodium Phytate (natural stabilizer), Lecithin (plant-derived softener), Tocopherol (vitamin E), Xanthan Gum (plant-based stabilizer), Sclerotium Gum (plant-derived stabilizer), Glyceryl Caprylate (plant-derived emulsifier), Capryhydroxamic Acid (plant-derived preservative). (68)

- All products ship plastic-free. All paper packaging is post-consumer and recycled FSC certified. Glass containers are from recycled glass. Post-consumer plastics include ocean waste plastics too.

Why It’s Awesome:

- I absolutely love all things Earth Harbor! It’s sustainably made magic in a recycled and recyclable glass jar. My face feels incredible, and it literally glows! See my full Earth Harbor Review for more!

- No synthetic ingredients/preservatives/fragrances, GMOs, fillers, petroleum, mineral oils, parabens, or phthalates.

- Clear! Unlike many zinc sunscreens, this one has no white caste.

- Fragrance Free. No banana scented sunscreen here!

Company Kudos

- ALL the certifications! PETA®, Leaping Bunny®, Climate Neutral®, Sustainable Forestry Initiative®, and Think Dirty® certified, as well as members of 1% For the Planet®, Campaign for Safe Cosmetics™, Truth in Labeling™, and Independent Beauty Association®.

- Ali Perry, Earth Harbor’s founder is a published researcher, certified health scientist, humanitarian engineer, and herbalist who specializes in global environmental health and toxicology. Now she uses her knowable to create sustainable, plant-based, and science-backed beauty products.

- Backs of product claims with peer reviewed research.

- Donates $1 to environmental non-profits for every product review on their site.

- Employs 40 local people at the solar-powder Utah lab.

- Hosts local beach cleanups at the Georgia administration office.

- Sources many non-GMO, organic, and sustainably wildcrafted ingredients from local farmers and herbalists.

- Seriously, Earth Harbor is setting the standard for sustainability awesomeness.

- Nearly 100% of packaging is locally sourced (within 50 miles)

- Women-owned business

(1)

For Me, Sunscreen Is Not Enough

Moisturize

I adore Earth Harbor, just see my Earth Harbor Review!

Here’s the other Earth Harbor products I pair my mineral sunscreen with:

- Aqua Aura Eye Cream

- Azure Regenerative Neck Cream (AMAZING for red splotchy skin)

- Luna Rain Resurfacing Serum

- Marina Biome Brightener

- Mermaid Milk Glow Moisturizer

- Sunshine Dew Oil Cleanser (The BEST way to get sunscreen off at the end of the day!)

- Peptide Face Serum

- Sea-Retinol Face Serum

- Siren Silk Hydration Cream

- Also available at Earth Hero®!

I gotta protect the skin I got, that means moisturize too.

Siren Silk and Sea-Retinol is packed with Sea Samphire (or sea fennel), a sustainable non-endangered plant with retinol-like functionality, antioxidants, and is source of non-synthetic Vitamin A. (69, 70, 71, 72)

The Peptide Face Serum can increase the production of collage and elastin in the skin thanks to seaweed peptides. (75, 76)

The Mermaid Milk contains Hyaluronic Acid, seaweed, spirulina, and matcha. That means it’s a skin-boosting powerhouse of moisture, antioxidants, and Vitamin C. Plus there’s Blue Tansy, which reduces redness. (76, 77, 86, 87, 88)

I put a drop of Sea Samphire and Celestine Peptides into the Siren Silk or Mermaid Milk for a treatment with a powerful combo of Vitamins C, E, B3, B5, Antioxidants, polyohenols, botanical hyaluronic acid, red algae, omega fatty acids, retinol, and peptides. (75, 76, 77, 78)

Combining these three products together gives my skin everything it needs.

And without the side effects or photosensitizing. (71, 72)

Research-backed, sustainably made, and plant-based skincare? Real results. Not false hopes. I’m all in.

Cover Up

Along with mineral sunscreen and moisturizer, I cover up.

Not only does this offer sufficient protection, but clothing coverage also saves money. I don’t go through so many sunscreen tins.

We don’t need to dish out big bucks for fancy UPF tops either. Regular clothing performs as well as specialized sun-protection clothing. (56, 57)

So, I ditched the bikini.

Too bad. I look so dang sexy in it.

Instead, I wear Patagonia’s Natural Rubber Yulex® 1mm Wetsuit and a big silly looking hat. I wear giant sunglasses that engulf my face and make me look like a bug.

Even in the summer, when temperatures are over 100 degrees, I wear long sleeve linen tops.

I’ve contemplated getting a parasol as well (I’ll keep you posted on that venture!). I imagine feeling rather grand going on walks carrying one.

Sun protection might not be skin-revealing-sexy. But if it means no more skin cancer surprises, then I’ll flaunt it with all I’ve got.

The Takeaway Message

I’ve had skin cancer, so good UVA/UVB sunscreen is a must.

Sunscreen can contain harmful chemicals and carcinogens. These might link to problems like neurotoxicity and coral reef bleaching. (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 16)

Legislative bans on these chemical sunscreens means safer alternatives are more available. (8, 9)

Non-nano zinc oxide or titanium dioxide for example. Make sure “non-nano” particles are used. Nanoparticles may contribute to genotoxicity and inflammation. (10, 11)

Sunscreen SPFs might not not live up to the claim. But without regulations, we are stuck with what we have. (23, 27, 28)

My favorite mineral sunscreens:

- Badger® Clear Zinc SPF 40 for body.

- Earth Harbor Eclipse Sunscreen for face. Also at Earth Hero®.

And I hydrate with the evidence-based skincare serums from Earth Harbor.

And I use less sunscreen overall by wearing a Natural Rubber Wetsuit and hats to cover up.

You don’t need any really fancy though. Regular, non-UPF clothing works. (56, 57)

Coving up means I use less sunscreen, so I can afford the higher cost of reef-friendly options.

That’s How i Healthy!

-Artemis

- Latha, M S, et al. “Sunscreening Agents: a Review.” The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology, Matrix Medical Communications, Jan. 2013, ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3543289/

- “Benzophenone.” ca.gov, https://oehha.ca.gov/proposition-65/chemicals/benzophenone

- Tibbetts, John. “Bleached, but Not by the Sun: Sunscreen Linked to Coral Damage.” Environmental Health Perspectives, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Apr. 2008, ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2291012/

- Horricks, Ryan A, et al. “Organic Ultraviolet Filters in Nearshore Waters and in the Invasive Lionfish (Pterois Volitans) in Grenada, West Indies.” PloS One, Public Library of Science, 24 July 2019, ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6655699/

- Ruszkiewicz, Joanna A, et al. “Neurotoxic Effect of Active Ingredients in Sunscreen Products, a Contemporary Review.” Toxicology Reports, Elsevier, 27 May 2017, ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5615097/

- Paul, Sharad P. “Ensuring the Safety of Sunscreens, and Their Efficacy in Preventing Skin Cancers: Challenges and Controversies for Clinicians, Formulators, and Regulators.” Frontiers in Medicine, Frontiers Media S.A., 4 Sept. 2019, ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6736991/

- Latha, M S, et al. “Sunscreening Agents: a Review.” The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology, Matrix Medical Communications, Jan. 2013, ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3543289/

- “The Republic of Palau Bans Sunscreen Chemicals to Protect Its Coral Reefs and UNESCO World Heritage Site.” The Republic of Palau Bans Sunscreen Chemicals to Protect Its Coral Reefs and UNESCO World Heritage Site | International Coral Reef Initiative, 2020. https://icriforum.org/the-republic-of-palau-bans-sunscreen-chemicals-to-protect-its-coral-reefs-and-unesco-world-heritage-site/

- B. Nomber 2571. State of Hawaii, Twenty-Ninth Senate Legislature, 2018. https://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/sessions/session2018/bills/SB2571_.htm

- Salmon, Robert. Tran, Dai. “Potential Photocarcinogenic Effects of Nanoparticle Sunscreens.” The Australasian Journal of Dermatology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2011, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21332685/

- Heng BC;Zhao X;Tan EC;Khamis N;Assodani A;Xiong S;Ruedl C;Ng KW;Loo JS; “Evaluation of the Cytotoxic and Inflammatory Potential of Differentially Shaped Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles.” Archives of Toxicology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2011, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21656222/

- Janaky Ranjithkumar, Akhila Sameesh, Hari Ramakrishnan, K. (2016). Sun Screen Efficacy of Punica granatum (Pomegranate) and Citrullus colocynthis (Indrayani) Seed Oils. Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci. 3(10): 198-206.

- Afaq, Farrukh, et al. “Protective Effect of Pomegranate-Derived Products on UVB-Mediated Damage in Human Reconstituted Skin.” Experimental Dermatology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, June 2009, ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3004287/

- Yayla, Muhammed, et al. “Potential Therapeutic Effect of Pomegranate Seed Oil on Ovarian Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury in Rats.” Iranian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Dec. 2018, ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6312678/

- Herbs, Mountain Rose. “Organics and Sustainability.” Organics and Sustainability, info.mountainroseherbs.com/organics-sustainability#organics.

- Matta MK, Florian J, Zusterzeel R, et al. Effect of Sunscreen Application on Plasma Concentration of Sunscreen Active Ingredients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. 2020;323(3):256–267. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.20747. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31961417/

- Comparison of ultraviolet A light protection standards in the United States and European Union through in vitro measurements of commercially available sunscreens. Wang, Steven Q. et al. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Volume 77, Issue 1, 42 – 47. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28238452/

- Diffey, Brian. “New Sunscreens and the Precautionary Principle.” JAMA dermatology 152,5 (2016): 511-2. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.6069. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26885870/

- “UV Radiation.” The Skin Cancer Foundation, skincancer.org/risk-factors/uv-radiation/

- Autier, P et al. “Sunscreen use and duration of sun exposure: a double-blind, randomized trial.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute 91,15 (1999): 1304-9. doi:10.1093/jnci/91.15.1304. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10433619/

- Autier, P et al. “Sunscreen use and intentional exposure to ultraviolet A and B radiation: a double blind randomized trial using personal dosimeters.” British journal of cancer 83,9 (2000): 1243-8. doi:10.1054/bjoc.2000.1429. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11027441/

- Autier, P. “Sunscreen abuse for intentional sun exposure.” The British journal of dermatology 161 Suppl 3 (2009): 40-5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09448.x. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09448.x

- Paul, Sharad P. “Ensuring the Safety of Sunscreens, and Their Efficacy in Preventing Skin Cancers: Challenges and Controversies for Clinicians, Formulators, and Regulators.” Frontiers in medicine 6 195. 4 Sep. 2019, doi:10.3389/fmed.2019.00195. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31552252/

- Wang, Lei, and Kurunthachalam Kannan. “Characteristic profiles of benzonphenone-3 and its derivatives in urine of children and adults from the United States and China.” Environmental science & technology 47,21 (2013): 12532-8. doi:10.1021/es4032908. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24073792/

- Kerdivel, Gwenneg et al. “Estrogenic potency of benzophenone UV filters in breast cancer cells: proliferative and transcriptional activity substantiated by docking analysis.” PloS one 8,4 e60567. 4 Apr. 2013, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060567. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23593250/

- Avenel-Audran, Martine et al. “Octocrylene, an emerging photoallergen.” Archives of dermatology 146,7 (2010): 753-7. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.132. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20644036/

- Diffey, Brian L et al. “Suntanning with sunscreens: a comparison with sunbed tanning.” Photodermatology, photoimmunology & photomedicine 31,6 (2015): 307-14. doi:10.1111/phpp.12190. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26139559/

- “Sunscreen Drug Products for Over-the-Counter Human Use.” Federal Register, 26 Feb. 2019, federalregister.gov/documents/2019/02/26/2019-03019/sunscreen-drug-products-for-over-the-counter-human-use

- “Melanoma of the Skin – Cancer Stat Facts.” SEER, https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html

- Neale, R E et al. “The effect of sunscreen on vitamin D: a review.” The British journal of dermatology 181,5 (2019): 907-915. doi:10.1111/bjd.17980. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjd.17980

- Young, A R et al. “Optimal sunscreen use, during a sun holiday with a very high ultraviolet index, allows vitamin D synthesis without sunburn.” The British journal of dermatology 181,5 (2019): 1052-1062. doi:10.1111/bjd.17888. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31069787/

- Passeron, T et al. “Sunscreen photoprotection and vitamin D status.” The British journal of dermatology 181,5 (2019): 916-931. doi:10.1111/bjd.17992. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31069788/

- Sizar O, Khare S, Goyal A, et al. Vitamin D Deficiency. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532266/

- Stokes, Caroline S, and Frank Lammert. “Vitamin D supplementation: less controversy, more guidance needed.” F1000Research 5 F1000 Faculty Rev-2017. 17 Aug. 2016, doi:10.12688/f1000research.8863.1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27594987/

- “Sun Protection and Vitamin D.” The Skin Cancer Foundation, 13 Aug. 2019, skincancer.org/blog/sun-protection-and-vitamin-d/

- “Clean Label Project, Sunscreen Heavy Metal Results.” Sunscreen Info-Graphic , 2018, https://cleanlabelproject.org/wp-content/uploads/Sunscreen_Infographic-01-1.jpg

- “Home.” Clean Label Project, https://cleanlabelproject.org/about-us/

- “Baby’s Mineral Sunscreen Lotion 50 SPF.” Kiss My Face, www.kissmyface.com/collections/kids-sunscreen/products/babys-mineral-lotion-spf-50.

- Valle-Sistac, Jennifer et al. “Determination of parabens and benzophenone-type UV filters in human placenta. First description of the existence of benzyl paraben and benzophenone-4.” Environment international 88 (2016): 243-249. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2015.12.034. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26773395/

- Jang, Hyun-Jun et al. “Safety Evaluation of Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) Compounds for Cosmetic Use.” Toxicological research 31,2 (2015): 105-36. doi:10.5487/TR.2015.31.2.105. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26191379/

- Bruze, M et al. “PABA, benzocaine, and other PABA esters in sunscreens and after-sun products.” Photodermatology, photoimmunology & photomedicine 7,3 (1990): 106-8.

- Ferguson, Kelly K et al. “Personal care product use among adults in NHANES: associations between urinary phthalate metabolites and phenols and use of mouthwash and sunscreen.” Journal of exposure science & environmental epidemiology 27,3 (2017): 326-332. doi:10.1038/jes.2016.27. https://www.nature.com/articles/jes201627

- Larsson, Kristin et al. “Exposure determinants of phthalates, parabens, bisphenol A and triclosan in Swedish mothers and their children.” Environment international 73 (2014): 323-33. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2014.08.014. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25216151/

- Urbach, F. “The historical aspects of sunscreens.” Journal of photochemistry and photobiology. B, Biology 64,2-3 (2001): 99-104. doi:10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00202-0. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11744395/

- Aldahan AS, Shah VV, Mlacker S, Nouri K. The History of Sunscreen. JAMA Dermatol.2015;151(12):1316. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.3011. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamadermatology/article-abstract/2471534

- Svarc, Federico. “A Brief Illustrated History on Sunscreens and Sun Protection.” Pure and Applied Chemistry, vol. 87, no. 9-10, 2015, pp. 929–936., doi:10.1515/pac-2015-0303. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2015-0303/html?lang=en

- Craddock PT (1998). 2000 Years of Zinc and Brass. British Museum. p. 27. ISBN978-0-86159-124-4.

- Tilmantaite B (March 20, 2014). “In Pictures: Nomads of the sea”. Al Jazeera.

- Moe, – J., et al. “Thanaka Withstands the Tests of Time.” Burma News International, 17 Sept. 2008, https://www.bnionline.net/en/mizzima-news/item/4971-thanaka-withstands-the-tests-of-time.html

- “Protect Land & Sea Sunscreen Cream Tin- Water Resistant SPF 40 I Badger Balm.” Badger Company, Inc, www.badgerbalm.com/p-1077-pls-reef-safe-sunscreen-cream-tin-spf-40.aspx. .

- “Protect Land + Sea Certification.” Haereticus Environmental Laboratory, HEL List, https://haereticus-lab.org/protect-land-sea-certification-3/

- “Badger Balm – Who We Are.” Badger Company, Inc, www.badgerbalm.com/s-13-who-we-are.aspx.

- “Badger’s Family Friendly Workplace.” Badger Company, Inc, www.badgerbalm.com/s-98-family-friendly-workplace.aspx.

- “Protect Land & Sea Sunscreen Cream Tin- Water Resistant SPF 40 I Badger Balm.” Badger Company, Inc, www.badgerbalm.com/p-1077-pls-reef-safe-sunscreen-cream-tin-spf-40.aspx. .

- “Badger Charitable Giving.” Badger Company, Inc, www.badgerbalm.com/s-24-charitable-giving.aspx.

- Bielinski K, Bielinski N. UV radiation transmittance: regular clothing versus sun-protective clothing. Cutis. 2014 Sep;94(3):135-8. PMID: 25279475. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25279475/

- “Sun Protective Clothing – Consumer Reports.” What We Found about the Effectiveness of Shirts with and without Built-in UV Protection, 11 Aug. 2015, consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/2015/05/testing-sun-protective-clothing/index.htm

- “Reef Safe Sunscreen Guide.” Reef Safe Sunscreen Guide | Save the Reef, https://savethereef.org/about-reef-save-sunscreen.html

- “Protect Land & Sea Sunscreen Cream Tin- Water Resistant SPF 40 I Badger Balm.” Badger Company, Inc, www.badgerbalm.com/p-1077-pls-reef-safe-sunscreen-cream-tin-spf-40.aspx. .

- “Protect Land + Sea Certification.” Haereticus Environmental Laboratory, HEL List, haereticus-lab.org/protect-land-sea-certification-3/.

- Tsatalis, John, et al. “Evaluation of ‘Reef Safe’ Sunscreens: Labeling and Cost Implications for Consumers.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, vol. 82, no. 4, 2020, pp. 1015–1017., doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.11.001. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31706942/

- “Sunscreen Contributing to Decline of Coral Reefs, Study Shows.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 21 Oct. 2015, theguardian.com/environment/2015/oct/21/sunscreen-contributing-to-decline-of-coral-reefs-study-shows

- Bever, Lindsey. “’We Have One Reef’: Key West Bans Popular Sunscreens to Help Keep Coral Alive.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 6 Feb. 2019, washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2019/02/06/we-have-one-reef-key-west-bans-popular-sunscreens-help-keep-coral-alive/

- “U.S. Virgin Islands’ Ban on Harmful Sunscreens.” Virgin Islands Conservation Society. https://viconservationsociety.org/advocacy/coral-safe-sunscreen/

- “Sunscreen Bans.” Com, https://stream2sea.com/sunscreen-ban/

- Rettner, Rachael. “Cancer-Causing Chemical Found in 78 Sunscreen Products.” LiveScience, Purch, 27 May 2021, livescience.com/sunscreen-carcinogen-benzene.html

- “Earth Harbor’s Sustainability Transparency Program.” Earth Harbor Naturals, https://earthharbor.com/blogs/news/earth-harbors-sustainability-transparency-program.

- “Eclipse Sheer Mineral Sunscreen.” EarthHero, https://earthhero.com/products/earth-harbor-naturals-eclipse-sheer-mineral-sunscreen.

- “Siren Silk Hydration Cream.” EarthHero, https://earthharbor.com/products/siren-silk-multi-tasking-hydration-creme.

- Shrestha, Sahara et al. “Pharmacognostical evaluation of Psoralea corylifolia Linn. seed.” Journal of Ayurveda and integrative medicine 9,3 (2018): 209-212. doi:10.1016/j.jaim.2017.05.005. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30121145/

- Hameury, Sebastien, et al. “Prediction of Skin Anti‐Aging Clinical Benefits of an Association of Ingredients from Marine and Maritime Origins: Ex Vivo Evaluation Using a Label‐Free Quantitative Proteomic and Customized Data Processing Approach.” Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, vol. 18, no. 1, 2018, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jocd.12528. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jocd.12528

- Caucanas, Marie, et al. “Dynamics of Skin Barrier Repair Following Preconditioning by a Biotechnology-Driven Extract from Samphire (Crithmum Maritimum) Stem Cells.” Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, vol. 10, no. 4, 2011, pp. 288–293., https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1473-2165.2011.00584.x

- “Samphire Sea-Retinol Digital Serum.” Earth Harbor Naturals, https://earthharbor.com/collections/products/products/samphire-sea-retinol-digital-serum.

- “Celestine Hydra-Plumping Peptide Serum.” Earth Harbor Naturals, https://earthharbor.com/collections/products/products/celestine-hydra-plumping-peptide-serum.

- Alboofetileh, Mehdi et al. “Seaweed Proteins as a Source of Bioactive Peptides.” Current pharmaceutical design 27,11 (2021): 1342-1352. doi:10.2174/1381612827666210208153249. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33557731/

- Pangestuti, Ratih et al. “Anti-Photoaging and Potential Skin Health Benefits of Seaweeds.” Marine drugs 19,3 172. 22 Mar. 2021, doi:10.3390/md19030172. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33809936/

- Jesumani, Valentina et al. “Potential Use of Seaweed Bioactive Compounds in Skincare-A Review.” Marine drugs 17,12 688. 6 Dec. 2019, doi:10.3390/md17120688. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31817709/

- Mukherjee, Siddharth et al. “Retinoids in the treatment of skin aging: an overview of clinical efficacy and safety.” Clinical interventions in aging 1,4 (2006): 327-48. doi:10.2147/ciia.2006.1.4.327. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18046911/

- Ibbetson, Fiona. “A History of Women’s Swimwear.” Fashion History Timeline, 24 Sept. 2020, https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/a-history-of-womens-swimwear/

- Kidwell, Claudia. “Women’s Bathing and Swimming Costume in the United States.” Smithsonian Institution Press, United States National Museum Bulletin, The Museum of History and Technology, 1968, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/37586/37586-h/37586-h.htm

- “Dressing for War.” National Museum of American History, Regulation L-85, 9 Nov. 2021, https://americanhistory.si.edu/explore/exhibitions/price-of-freedom

- Martin, Jo M et al. “Changes in skin tanning attitudes. Fashion articles and advertisements in the early 20th century.” American journal of public health 99,12 (2009): 2140-6. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.144352. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2775759/

- Gause, S, and A Chauhan. “UV-blocking potential of oils and juices.” International journal of cosmetic science 38,4 (2016): 354-63. doi:10.1111/ics.12296. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26610885/

- Goldsberry, Anne et al. “Thanaka: traditional Burmese sun protection.” Journal of drugs in dermatology : JDD 13,3 (2014): 306-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24595576/#:~:text=Unique%20to%20the%20Burmese%20people,can%20be%20found%20in%20museums.

- Wangthong, Sakulna et al. “Biological activities and safety of Thanaka (Hesperethusa crenulata) stem bark.” Journal of ethnopharmacology vol. 132,2 (2010): 466-72. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.08.046. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20804839/

- Pazyar, Nader et al. “Green tea in dermatology.” Skinmed vol. 10,6 (2012): 352-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23346663/

- Draelos, Zoe Diana et al. “Efficacy Evaluation of a Topical Hyaluronic Acid Serum in Facial Photoaging.” Dermatology and therapy vol. 11,4 (2021): 1385-1394. doi:10.1007/s13555-021-00566-0. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34176098/

- Health Line, “What Are the Benefits of Blue Tansy?”, https://www.healthline.com/health/blue-tansy#benefits.